You can write an original song in 15 minutes—without AI

No musical knowledge required, just follow these two simple rules

“Anyone can play guitar,” or at least that’s what Radiohead taught us. It’s a wonderful song, but I’m not sure I agree. Guitars are super confusing to me.

As a musician, I guess I’m sort of a math geek. In my head I picture the notes of a chord as a simple number set like 1, 3, 5. So for me, trying to form chords on a guitar is like trying to do Euclidian geometry without knowing how to add or subtract. A simple three-note G chord suddenly becomes a long series of x, y coordinates: [1, 3], [2, 0], [3, 0], [4, 0], [5, 2], [6, 3]. Yes, that’s actually how you play an open G chord on guitar.

While I’m at it, Mr. Guitar, why is the exact same note found in different places on different strings? What is this, some kind of freaky quantum physics phenomenon? Schrödinger’s catgut? (Musician dad jokes, hahahaha.)

“Whenever I feel like ‘noodling around’ to find some new chords, I’m almost always drawn to the keyboard instead of the fretboard.”

Anyway, this is surely why I only play a tenor guitar: making chords is far simpler with only four strings. It’s probably also why, whenever I feel like “noodling around” to find some new chords that could become a song, I’m almost always drawn to the keyboard instead of the fretboard.

Now, I understand that pianos can also seem foreboding to the budding musician, and not just because they’re super expensive and awkward to carry around. We’ve all been conditioned to believe that playing piano requires some kind of naturally prodigious Beethoven-esque talent. Or lacking that, then years of relentless tutoring under a grim spinster holding a wooden ruler. These myths are why there’s no song called “Anyone Can Play Piano.”

The shocking truth

The real shocking truth, which the guitar-industrial complex has conspired to hide from you but that I will nonetheless now speak fearlessly, is this: building chords on a piano is much, much simpler than guitar.

And I will further tempt fate and internet ridicule by asserting that if you have ever wanted to write your own pop song, sitting down at a piano—especially if you’ve never played any instrument before—is actually the best way to go. Importantly, using this method is also much more likely to result in a tune that actually sounds like you, instead of just like a super-lazy cover of The Beatles.

Skeptical? Read on and give it a try.

By the way, you don’t need a Steinway for this. You can find a very lovely little midi keyboard that plugs into your laptop for under $40, far less than the cost of any guitar. For now, you can even just pop open Garageband, or some random piano app on your phone or tablet. Literally any keyboard that makes noise will do, even a virtual one.

So here are my two simple rules for non-musicians who want to write an original song using a piano. (And neither of them is “Just play the white keys.” Don’t use that rule, it’s stupid and boring, maybe even racist.)

The Spacing Rule

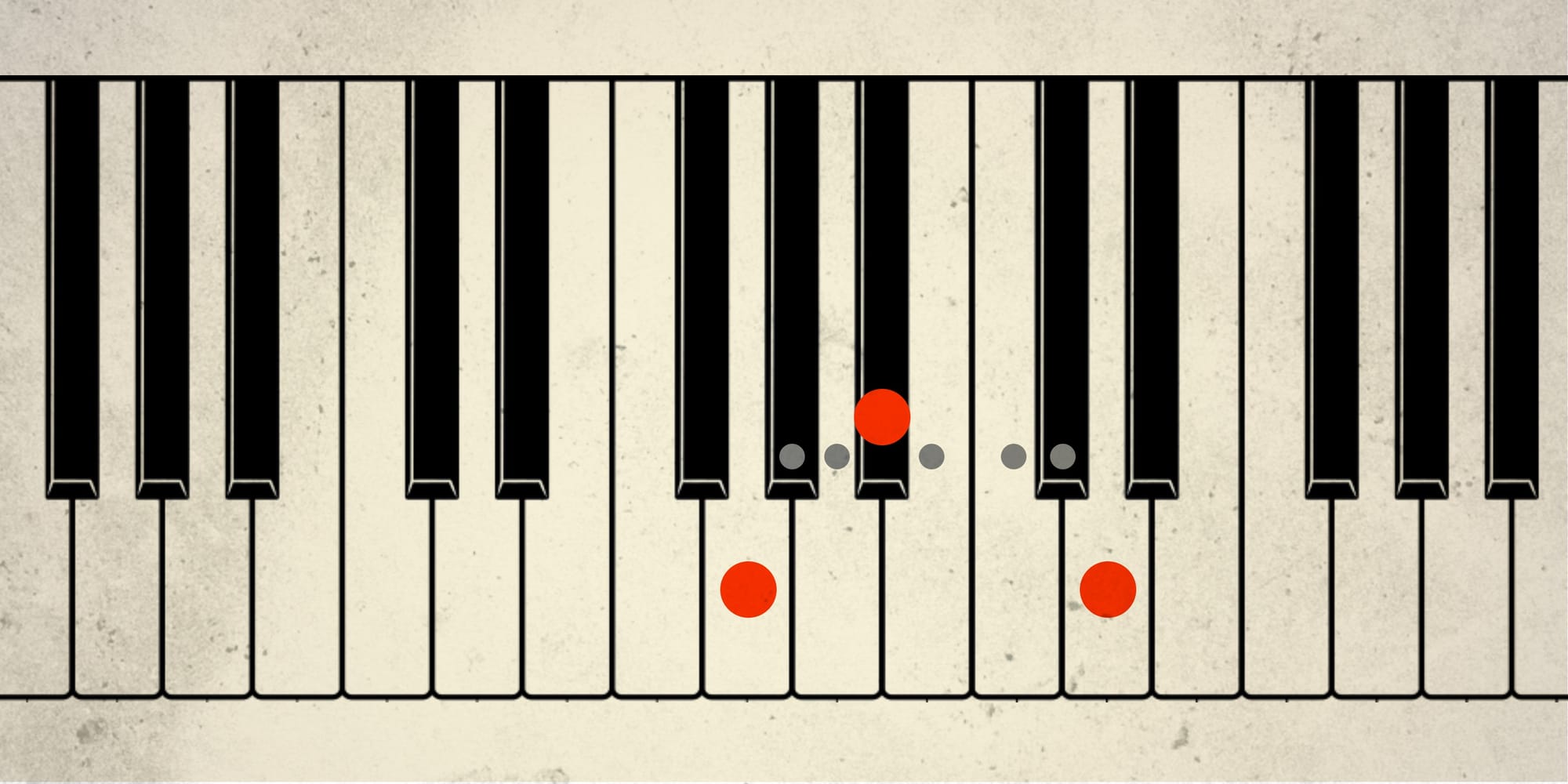

Play any 3 notes you want, just leave 2-4 “spaces” between them.

Technically, any three or four random notes that you hit within an octave make a chord. Some of them are quite common, like C major or E minor, and others are rarely ever used in pop music and have very long and complicated names, like “A#6sus2\D#.” But they are all chords.

Just pick any three notes you want, as long as each note has either 2, 3, or 4 unplayed keys between it and the next note. You don’t need to know the names of the notes, or know anything about sharps or flats or suspended intervals, or even—heaven forbid—understand the circle of fifths (I still don’t). You don’t even need to know what an octave is.

See? You’ve just made a lovely chord. Don’t love it? No problem, pick another. I can go all day doing this. Some of your chords might sound sort of weird, and that’s because they are. But the nice thing about the spacing rule is that it only allows them to be sort of weird (and in a beautiful way, imho). So feel free to follow your weird, you can’t go very wrong.

Why do you need a spacing rule? This is more than you need to know, but there are two potential chord pitfalls that it helps you avoid, while still allowing for many, many wonderful chord permutations.

First, if two of the notes in your chord are too far apart, you may just be playing the same note but in a different octave. In that case your chord effectively has only two notes instead of three, which demotes it from a chord to just an interval.

Second, if any two notes are too close together, then they’re going to sound “dissonant.” There’s nothing wrong with dissonance, especially if you’re a rebel like Schoenberg. But no one would call his work pop music. For now let’s just say that using dissonance well is a more advanced concept.

The Movement Rule

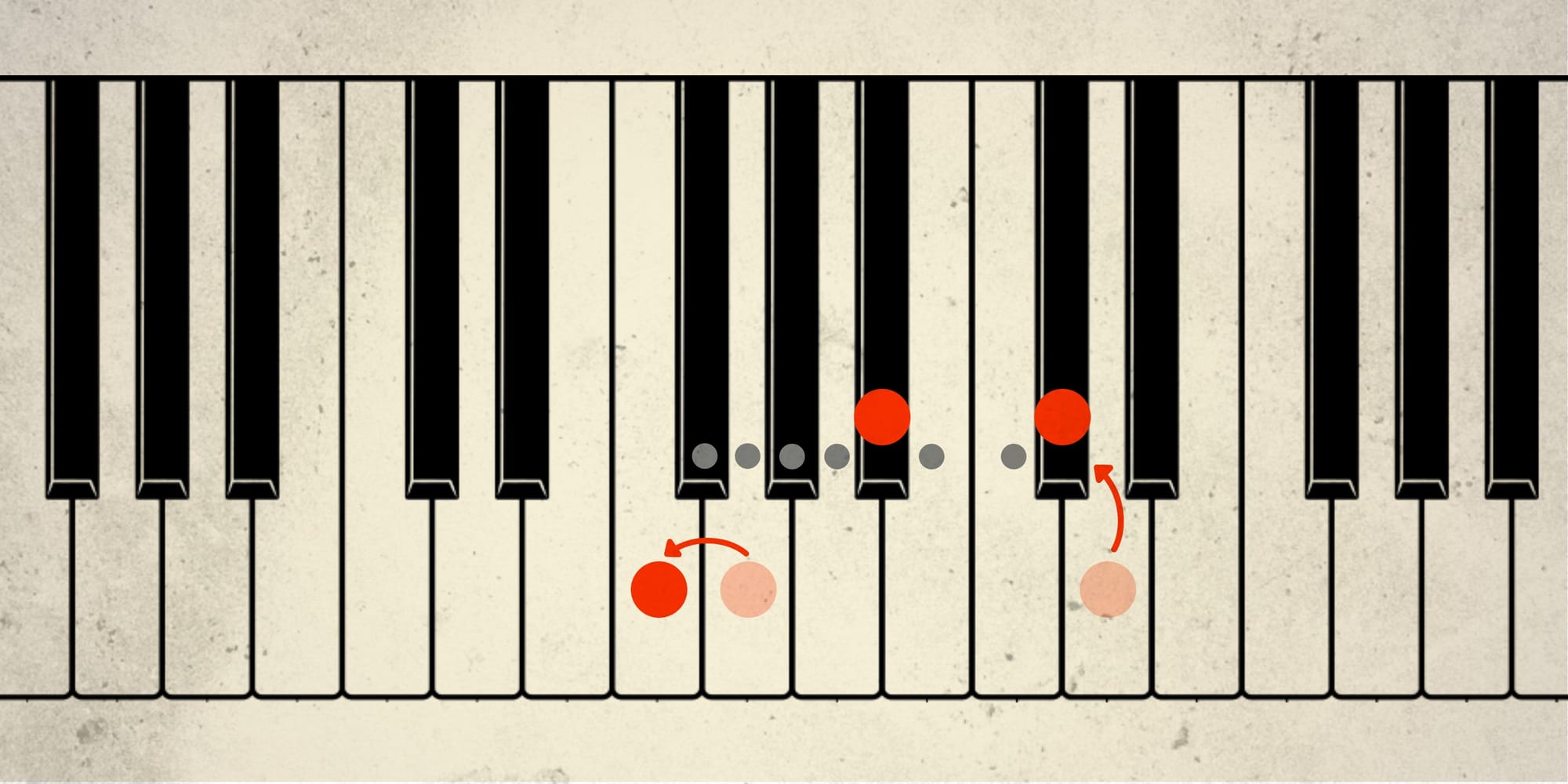

For your next chord, just change 1 or 2 fingers while maintaining the spacing rule.

It’s that simple: move either one or two fingers to new notes. Just move them in a direction that won’t break the spacing rule.

So for example, if you already have four spaces between your top two notes, move them closer together, not further apart. Similarly, if you have only two spaces between two notes, then move them away from, not toward, each other.

Why do we need a movement rule? It’s just an easy way of following some of the “laws” of classical harmony (which pop songs almost invariably follow) without having to actually know them. Your piano won’t explode if you break this rule, it’s just a way of staying within a range of chord progressions that will generally sound pleasing, but still keep things interesting.

Wait, my chords sound too weird!

Okay, if you follow the example in the images above, it begins as a pretty “weird” chord progression, going from G minor to Bb minor. I doubt you’ll find that particular sequence in any Beatles songbook. But to my ear, it sounds kind of interesting, and I could definitely see writing a song that starts that way. Try playing just those two chords back and forth a few times and I think you’ll see what I mean.

However... if you end up with chords that just sound too weird to you, no problem! Just move one of your fingers to a different note and chances are quite high that you’ll land on a chord you like better. In fact, in the above example, if you just kept your top finger still instead of moving it down one note, then your song goes from G minor to Bb major, which is a classic move. And you did that by only moving one finger! Harmony is amazing.

But I’ll say it again: don’t be too afraid of weird. The fact that you can easily find unconventional chord pairs is kind of my jam here. Writing songs this way gives you a far better chance of discovering something interesting and unique, instead of just reinventing the exact same G / B / D song that everyone writes when they get their first guitar.

So don’t give up on weird chords too quickly. Sometimes, if you just keep playing them over and over, they’ll start to sound less weird to you, and pretty soon you’ll find yourself humming an original melody over the top of them.

Now what?

Okay, so now you have two chords. Many pop songs have been written with only two chords, but I think you’ll like it better if you use three or four chords in a sequence. So all you have to do is repeat the movement rule until you have as many chords as you want!

At this point you’re going to want to keep track of the chords you’ve made, so I recommend some kind of simple labeling system on the keys. Use numbers written on sticky notes or color dots or whatever makes sense to you to identify which keys go to which chord so you can play them in sequence without getting confused. If you’re using a virtual keyboard, you can take a screenshot while you play each chord. After you repeat them a bunch of times, your fingers will start to remember the positions and it will get easier.

Once you reach that point, you’re ready to start adding a melody and some lyrics! But ... I’ll save that for Part 2 since this post is already super lengthy. So stay tuned for more. In the meantime, go make up some weird chords!